×

In early September, at the end of our trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico, we crush out to Bandelier National Monument. We’d last explored its warmed-over cliff dwellings and pueblo ruin two decades earlier, and we wanted to hike and see it again.

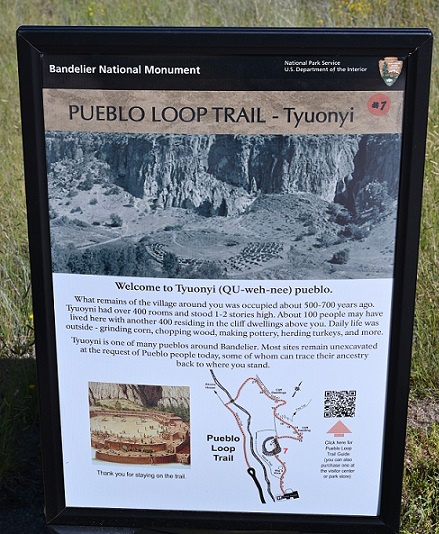

We took the scenic Pueblo Loop Trail, which winds through Frijoles Pass and withal tall cliffs of soft, volcanic waddle tabbed tuff. Late summer/early fall wildflowers were visculent withal the trail.

Frijoles Pass is quietly scenic today, but approximately 800 years ago it was home to hundreds of ethnic people who farmed, hunted, foraged, and raised turkeys. They made homes and storage places in hollowed-out caves in the cliffs and built multi-story, stone-and-mud structures on the pass floor. The park’s website offers this history:

“The Ancestral Pueblo people lived here from approximately 1150 CE to 1550 CE. They built homes carved from the volcanic tuff and planted crops in mesa top fields. Corn, beans, and squash were inside to their diet, supplemented by native plants and meat from deer, rabbit, and squirrel. Domesticated turkeys were used for both their feathers and meat while dogs assisted in hunting and provided companionship. By 1550, the Ancestral Pueblo people had moved from this zone to pueblos withal the Rio Grande. Without over 400 years the land here could no longer support the people and a severe drought widow to what were once rhadamanthine difficult times.”

Today you can explore the pass and plane enter some of the caves at Bandelier, named for Adolph Bandelier, a 19th-century anthropologist whose work here drew sustentation to the importance of the site, sooner leading it to be preserved as a national monument.

Along the trail to the cliffs you come wideness Big Kiva. A kiva is a circular, subterranean space for religious ceremonies or communal gatherings, accessed via a ladder in a roof made of posts and mud. The roof of Big Kiva is long gone, but the stone whirligig remains.

A smaller kiva has been excavated a little farther withal the trail.

Ruins of stone woodcut homes can be seen nearby.

According to signage, well-nigh 100 people may have lived in houses on the pass floor, and flipside 400 in cavates (pronounced CAVE-eights), or carved-out caves, in the tall cliff withal one side of the canyon. In the summer they farmed on the mesa atop the cliff. Imagine scrambling to the top of that to tend your crops!

You’re unliable to enter the cavates that have ladders. A ranger told us that the native Puebloans would have made ladders out of a single pole with notches cut out for footholds, or by lashing wooden rungs to two poles. Can you imagine darting up a single-pole ladder to wangle your home, perhaps delivering an infant or supplies supplies? In all weather?

And yet they did. According to Bandelier’s website:

“Over a thousand of these rooms are located in the walls of Frijoles Canyon…Groups of these homes, cavate villages, were used by generation without generation of Ancestral Pueblo people…Gouges in the ceilings of cavates show that builders used tools such as digging sticks and sharpened stones to overstate naturally occurring openings in the tuff. Most cavates are single rooms, but some are unfluctuating by interior doorways. Many cavates were fronted with masonry structures up to three stories upper that were synthetic of tuff blocks and mud mortar…These rooms were used for many things including weaving, grinding corn, and storage. Many cavates contain carved and plastered niches, probably for storing pots and household items. Sockets in the ceiling, withal with anchors set in the floor, held supports for looms that were used for weaving. The cavates were moreover used as living quarters.”

A room with a view

The cavates overlook the ruins below, known as Tyuonyi Pueblo.

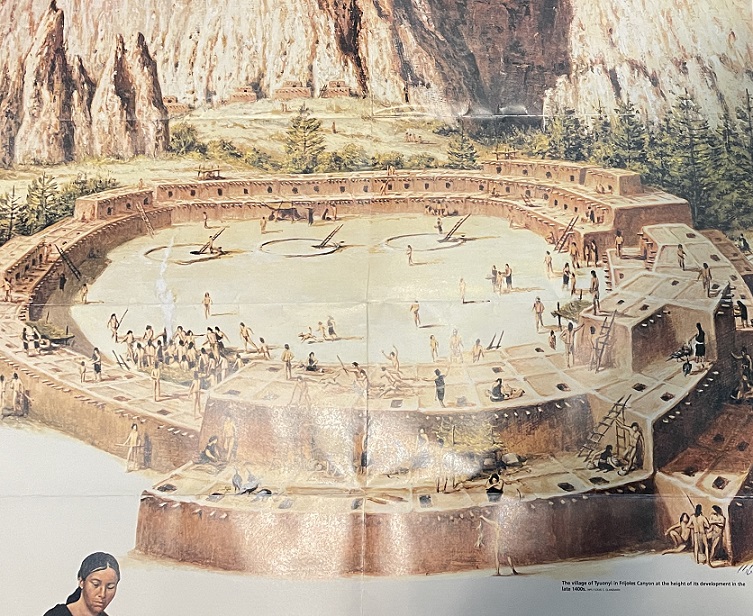

Built in a circle, the foundation ruins show where a lively village of multi-story rooms would have stood 800 years ago…

…as represented in this image from the National Park Service brochure. The circles in the part-way with ladders poking out of them are kivas. Versus the cliff wall in the preliminaries are masonry structures fronting some of the cavates.

Along the cliff, Talus House is an early 1900s reconstruction of the masonry structures that would have fronted some of the cavates. It likely would not have had a window or door; the existing window is there so visitors can squint inside. Rather, it would have been wieldy via a ladder in the roof.

The Ancestral Pueblo people must have been whiz climbers.

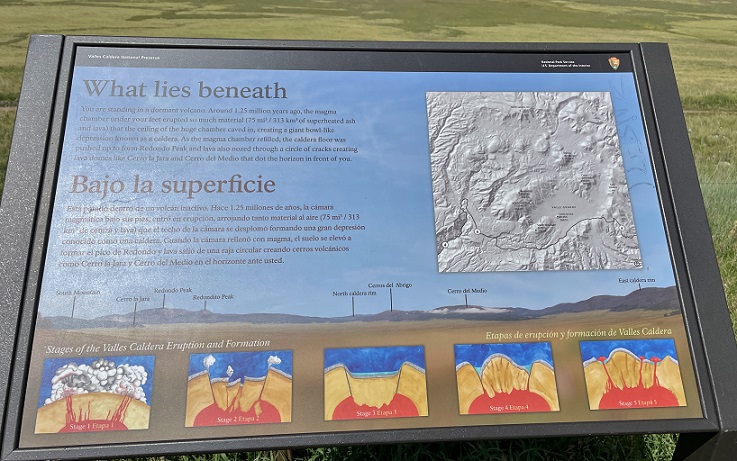

The soft and holey volcanic waddle in Frijoles Pass came from ash flows from Valles Caldera, which we visited later that day (pics below).

These eroded stone pillars squint like people, don’t they? One is sitting, the other standing, gazing out at the canyon.

We fancied we saw a skull in one section of the cliff.

View when toward Talus House

Cholla and wildflowers

More wildflowers

One section of the cliff shows vestige of multi-story homes built versus the cliff wall. This is tabbed Long House.

Rows of holes in the soft waddle show where wooden poles tabbed vigas once supported the roofs.

Hundreds of petroglyphs — some of turkeys and dogs — remain to this day, carved into the stone, providing vestige of how the people lived.

A painted pictograph survives too, now protected under glass.

Datura and red morning glory, growing wild

More cholla with wildflowers

A sphinx moth wearing the same hues as the pictograph wrapped me here, darting and swooping among the flowers, nectaring with its long tongue.

Zoom — a fly-by!

Dining on the wing

Canyon view

The trail continues flipside half-mile toward Alcove House and dips into a woodland, where we were lucky to spot this heady cannibalizing scene. Sorry for the blurry pic taken from a distance, but that’s a larger snake on the right devouring a still-struggling smaller snake on the left. The smaller snake had locked its tail virtually something to try to pull away, but the worthier snake overpowered it, swallowing half surpassing slithering away, a drooping tail pendulous from its mouth.

On previous visits we’d never gone as far as Alcove House, a large grotto tucked 140 feet up a cliff face. David was excited to climb up to it. It’s wieldy via 4 wooden ladders and stone stairs. I decided to pass, remaining unelevated to take photos of his climb.

There he goes.

He took this photo looking up the third ladder.

And here’s his view from inside. A reconstructed kiva sits here, and 25 people may have lived in this upper grotto at one time.

Of undertow if you go up, you must go down.

Bandelier is fascinating, and we were glad for the endangerment to explore it again. Without a picnic lunch we crush 30 minutes west to Valles Caldera National Preserve — the origin of all the volcanic waddle at Bandelier. Where once there was testatory destruction, today a trappy untried valley spreads out surpassing you.

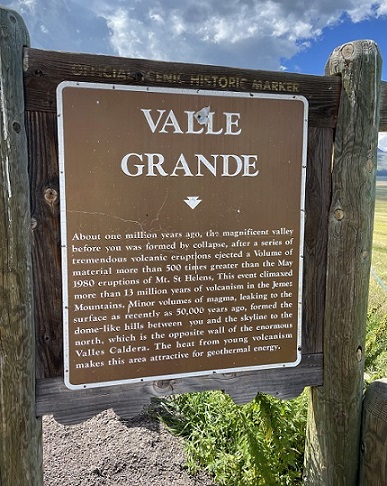

A bullet-holed sign tells the story:

“About one million years ago, the magnificent valley surpassing you was worked by collapse, without a series of tremendous volcanic eruptions ejected a volume of material increasingly than 500 times greater than the May 1980 eruptions of Mt. St. Helens…Minor volumes of magma, leaking to the surface as recently as 50,000 years ago, worked the dome-like hills between you and the skyline to the north, which is the opposite wall of the enormous Valles Caldera.”

“You are standing in a unseeded volcano,” a sign explains. I’ve been to a few of these in my lifetime.

The valley grasses glowed mossy green, with moody, blue-green hills all around. It was gorgeous.

Prairie dogs make their homes here, and the cute rodents were standing up and dashing wideness the road while we stopped to watch them.

From there we crush to Los Alamos, where we discovered that every car is stopped at the archway to town by security, asked their merchantry there, and — when your camera is spotted on the panel — told not to photograph the buildings on the right side of the road as you momentum in. Okay then! I ended up not taking any photos in Los Alamos, as we simply crush through, but it satisfied our morbid marvel to see the municipality where the two-bit flop was developed.

On the way out of town, heading when to Santa Fe, we came to a scenic view of orange mesas skirted by olive untried trees, with undecorous mountains in the distance. We pulled over at the Anderson Scenic Overlook to take in yet flipside stunning vista in the Land of Enchantment, on our last day in New Mexico.

This is my final post well-nigh our end-of-summer road trip to New Mexico. To read the series, visit my post well-nigh Santa Fe Railyard Park and Farmers’ Market and work wrong-side-up from there, finding spare links at the marrow of each post.

I welcome your comments. Please scroll to the end of this post to leave one. If you’re reading in an email, click here to visit Digging and find the scuttlebutt box at the end of each post. And hey, did someone forward this email to you, and you want to subscribe? Click here to get Digging delivered directly to your inbox!

__________________________

Come learn well-nigh garden diamond from the experts at Garden Spark! I organize in-person talks by inspiring designers, landscape architects, and authors a few times a year in Austin. These are limited-attendance events that sell out quickly, so join the Garden Spark email list to be notified in advance. Simply click this link and ask to be added. You can find this year’s speaker lineup here.

All material © 2022 by Pam Penick for Digging. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited.

The post Bandelier cliff dwellings, Valles Caldera, and epic New Mexico scenery appeared first on Digging.

.